PDF

588KB

Drama – Teacher-in-role guide

Why use teacher-in-role?

Most learning in drama, and even teaching through process drama, can be achieved by the 'normal' teaching strategies where the teacher is the guide, facilitator and instructor. However, far more can be achieved if the teacher is prepared to enter the fiction. The teacher can take on a role ('teacher-in-role') to enrich the action and simultaneously shift the power and status in the classroom, which allows the students to be empowered beyond their normal roles.

If you feel you have few drama skills, you may feel nervous stepping into role. Many teachers don't want to make a fool of themselves or lose their authority. However, there are several inescapable reasons why you should not be afraid to step into role and why it will expand your teaching immeasurably.

Firstly, you will be genuinely sharing in the children's learning. Working in drama permits you to do something that's not possible in any other classroom context: safely suspend the normal order of status and authority. Principles of good teaching stress the importance of accessing the children's knowledge and scaffolding their learning upon it. So often we begin with their supposed ignorance, by virtue of the fact of our age, authority and the knowledge of the curricular area that we have acquired. Often we ask questions that we already know the answer to, where the children are reduced to guessing the answer that is already in our heads. By taking role as somebody who does not know, or who needs help, or who merely brings a message, the responsibility of finding out and communicating what needs to be known is placed on the children. They are allowed temporarily to acquire and control the expertise; they wear 'the mantle of the expert'1.In turn, you will be modelling effective learning behaviour when in-role, just as you do in all other subjects.

Secondly, if the children can see that their teacher is taking the drama seriously, and being involved in it, this will reinforce their own seriousness (though it might take some practice before they are comfortable with the teacher joining in and encouraging their play in the classroom). By the time children get to school they are already very skilled in pretend and dramatic play. It is important not to forget that you still have the same skills from your own childhood. In fact, you have more than they do, namely command of language register, vocabulary, gesture and movement, all of which are important to model for the children.

In language terms, drama offers wonderful possibilities for gaining control of new language registers, both verbal and gestural. When behaving as reporters addressing a Maharajah or interviewing a timid mother, the children need to speak and act appropriately based on the social protocols and conventions. Teacher-in-role allows you to model these registers.

Thirdly, teacher-in-role empowers the teacher to manage the structure and alter the action while the drama is running, instead of being stranded on the sidelines and having to continually stop the drama. In-role, you can provide a lead and also incorporate fresh, important contextual information indirectly such as, 'From my experience in reporting current affairs, I think there are things much more worthwhile to spend the treasure on than those ideas of the Maharajah's'.

Fourthly, far from potentially undermining your real authority in the classroom, teacher-in-role gives you a whole new set of disciplining tools for that suspended, but still real, classroom. If a pair of students do not take the interview seriously, or a student is off task and tries to get smart when interviewing a townsperson or child labourer, rather than stopping the drama to reprimand those children or set them on task again, you can intervene in-role as the producer to remind them that the success of the program, and possibly any influence that might be had on the treasure, depends on getting good interview copy. If you adopt the child labourer role, you have an even more powerful discipline tool, because shrinking away with a look of sadness will immediately get the rest of the group to discipline their (cheeky) fellow classmate/s quite emphatically!

Drama of this nature gives you more opportunities for classroom control. Once you have conquered your initial trepidation, and the children's initial surprise, you will have a lot of fun yourself!

What you need

- Seriousness, belief and the willingness to background the role appropriately

- Not to 'act', but be yourself, using appropriate language and non-verbal signals, understanding the right status signals

- To signal clearly, especially on moving into or out of role

- Clear and appropriate spatial positioning; that is, be sure that you, as the teacher-in-role, are the centre of focus only when necessary, and if students are in-role as adults in a meeting or interview, use chairs and not the floor

- A clear and specific purpose and tasks for the students, such as a need to know or a desire to help

- Possibly one prop or characteristic gesture to help indicate when you are in-role

- To hold your nerve and stay in-role long enough to give the students time to adjust and believe in the situation.

What you don't need

- Attempts to act artificially, or put on an accent

- To choose a leadership role of information giver and controller, as this is too close to your everyday role as the students' teacher

- Elaborate costumes or props

- To do all the talking; less is more, as the students have to work harder to gain information/provide support (see below)

- The yahoo effect (see below: Types of teacher-in-role).

Status, power and purpose in the classroom

In the normal primary classroom, for most of the time, teachers have higher status than the students due to their:

- age

- size and strength

- experience

- authority that comes with the school and its rules

- authority that is also vested in being in statu parentis

- knowledge and skills (except rarely, when students may bring their own specialised knowledge)

- curriculum knowledge, skills and understanding.

The above conditions are usually rather one-sided and result in the teacher providing information, help, or support for most of the time; negotiating, planning or discussing on equal terms much less of the time; and rarely genuinely seeking information, help or support. Good teachers often frame tasks to appear to be seeking an answer with the students, where, as the students know, we are merely withholding our knowledge to let them have a go. This is normal and necessary in many situations. However, it does mean that the students are rarely able to hold either power or status in a classroom (except over each other), and often their day is spent in dependent activity rather than independent agency. The drama lesson offers a powerful exception to that, as drama allows us to turn the classroom into any fictional world we like, and alter the power dynamic.

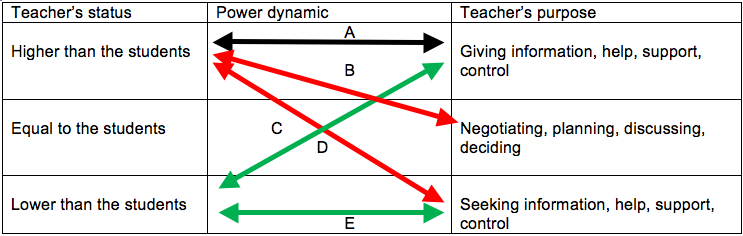

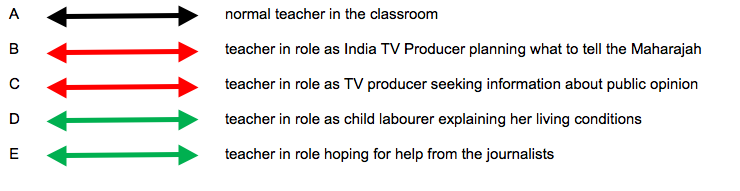

The following diagram demonstrates these dynamics from the teacher's point of view (with examples from this drama):

Lines B, C, D and E all show how within the dramatic world, the teacher could genuinely change the standard pattern of classroom interaction to give the students power and status, at least within the dramatic context. The students were then able to use all of these opportunities seriously and intelligently, taking responsibility and agency with great pride.

Types of teacher-in-role

The following teacher-in-role stances are some of those available and often used, and which stance is chosen depends on the dramatic context and the purposes of the students-in-role. Examples of different types of roles are listed below.

- The person who knows or has vital information (such as the child labourer)

If at all possible, teachers' roles should be of equal or lower status than the students’. It is also very valuable to build in a constraint to make the information difficult and more of a challenge to obtain.

- The person who does not know (such as the TV producer who needs to find out public opinion, or the alien trying to find out about earthling society)

- The person who needs help or object of sympathy (such as an elderly person in danger of losing their home)

- The messenger or intermediary (such as the Royal Ambassador) who can take messages and report on how they are received, but has no power

- The chairperson or umpire (such as the town mayor, who needs to get the village’s agreement or consensus)

- The object of controversy or confrontation (such as the Pied Piper or Scrooge). Note: if taking this role, the teacher should provide a challenge by working away from the students' expectations

This role is more for the experienced teacher as, if it not handled with care, it can lead to the 'Yahoo' effect where the class gangs up on the antagonist. This result is usually undesirable, as it is driven by mob excitement and the unexpected freedom drama provides to let off steam, rather than give a thoughtful and mindful response. It may also challenge the teacher’s real power under the guise of the drama.

- The leader and giver of information, but beware (see diagram, line A): this is the kind of role you may feel most comfortable to try first, but it often becomes difficult to avoid playing the teacher, thereby abandoning all the above reasons for using teacher-in-role in the first place.

1In the words of the drama teaching pioneer, Dorothy Heathcote, who was also a pioneer of using teacher-in-role: see Heathcote, D. & Bolton, G. (1995). Drama for Learning: Dorothy Heathcote's Mantle of the Expert Approach to Education. Portsmouth, NH.: Heinemann.